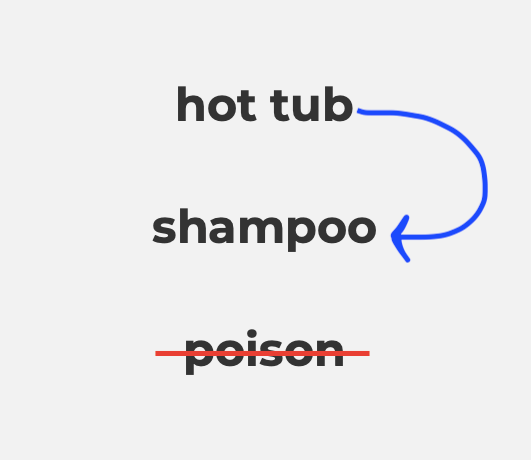

Okay, so there’s the obvious route: Hot tubs are like bathtubs, where you’d usually use shampoo. But there’s not much science along that path. Let’s see if we can forge another one.

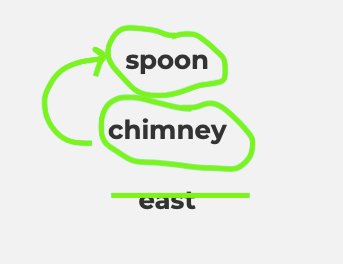

Hot tubs are so relaxing because heat loosens our muscles, which is a big-picture way of saying that blood vessels dilate when they’re warm—letting our bodies transport bad stuff out of muscles and good stuff into them. (That itself is a big-picture way of avoiding biology.) There’s probably some biochemistry that goes into dilating warm vessels (there definitely is), but there’s also some pretty straightforward physics. Something’s temperature is a measure of the internal kinetic energy of its atoms and molecules: The hotter the object, the more its molecules wiggle and jiggle. Cold things tend to be rigid because their molecules don’t have the energy they’d need to adjust their positions much. Warmer things loosen up, and they also tend to expand: their molecules can spread out now that they have the energy to push their surroundings out of the way. The same must be true for the walls of blood vessels.

This is fundamentally why we clean with hot water, too. It gives grimy molecules the energy they need to break free from whatever they’re affixed to. An awful lot of kinds of molecules dissolve in water, so anything loosened by the heat tends to be carried away by the water. Washing with soap and hot water is even better—at least as far as dirt is concerned. Soap molecules either bond with or otherwise break into bits of oil or dirt, and it’s easier of molecules to react and rearrange when they have a lot of energy.

Ridding any surface of oils and dirt is the central job of any soap. Soaps get specialized because we might not care very much if a soap is designed to mount an all-out attack on a plate (ceramic can handle it), but we’d probably care more about a soap that does such a good job cleaning our hair that it destroys the hair in the process. That’s why we use gentler stuff on our hair: Shampoo might not be quite as good at breaking bonds as dish soap, but the trade-off is worth it for something made to be gentle. We also want stuff in our hair that washes away easily, and shampoo is designed to be just that.

There. That was a more interesting route, huh?